The title of this post is borrowed from Walter Brueggemann’s essay “The Costly Loss of Lament” (1986). If you are interested in reading it you can download it HERE. (ALERT, it is not a tweet!)

Lament has been and continues to be a subject of deep interest to me. You can read my previous posts on lament HERE.

Experiencing a pandemic which has spawned financial and political crises, followed by social upheaval has not lessen my interest in lament, in fact, it has increased it. Hopefully, this post will make clear why that is so.

Motivation for this post also comes via Christian responses to those events.

There are three parts to this post, 1) Citations from Brueggemann’s essay, 2) A story from our foster parenting days, and 3) Thoughts on loss of lament

The Costly Loss of Lament

As implied, Brueggemann’s premise is that lament has been lost. He asserts that loss is because lament Psalms are no longer a part of life and liturgy in the faith community. His comments are worthy of serious study. For the purposes of this posts, I accept his premise, and will share some quotes regarding losses incurred when lament is absent.

Lament occurs when the dysfunction reaches an unacceptable level, when the injustice is intolerable and change is insisted upon.

What happens when the speech forms [lament] …have been silenced and eliminated? The answer, I believe, is that a theological monopoly is re-enforced, docility and submissiveness are engendered, and the outcome is to re-enforce and consolidate the political- economic monopoly of the status quo. That is, the removal of lament from life and liturgy is not disinterested and, I suggest, only partly unintentional.

One loss that results from the absence of lament is the loss of genuine covenant interaction because the second party to the covenant (the petitioner) has become voiceless or has a voice that is permitted to speak only praise and doxology. Where lament is absent, covenant comes into being only as a celebration of joy and well-being.

The absence of lament makes a religion of coercive obedience the only possibility.

Where the lament is absent, the normal mode of the theodicy question is forfeited. When the lament form is censured, justice questions cannot be asked and eventually become invisible and illegitimate. Instead we learn to settle for questions of ‘meaning?, and we reduce the issues to resolutions of love. But the categories of meaning and love do not touch the public systemic questions about which biblical faith is relentlessly concerned. A community of faith which negates laments soon concludes that the hard issues of justice are improper questions to pose at the throne, because the throne seems to be only a place of praise.

…it thus follows that if justice questions are improper questions at the throne (which is a conclusion drawn through liturgie use), they soon appear to be improper questions in public places, in schools, in hospitals, with the government, and eventually even in the courts. Justice questions disappear into civility and docility. The order of the day comes to seem absolute, beyond question, and we are left with only grim obedience and eventually despair. The point of access for serious change has been forfeited when the propriety of this speech form is denied.

Psalm (39) characteristically brings to speech the cry of a troubled earth (v. 12). Where the cry is not voiced, heaven is not moved and history is not initiated. And then the end is hopelessness. Where the cry is seriously voiced, heaven may answer and earth may have a new chance. The new resolve in heaven and the new possibility on earth depend on the initiation of protest.

It makes one wonder about the price of our civility, that this chance in our faith has largely been lost because the lament Psalms have been dropped out of the functioning canon.

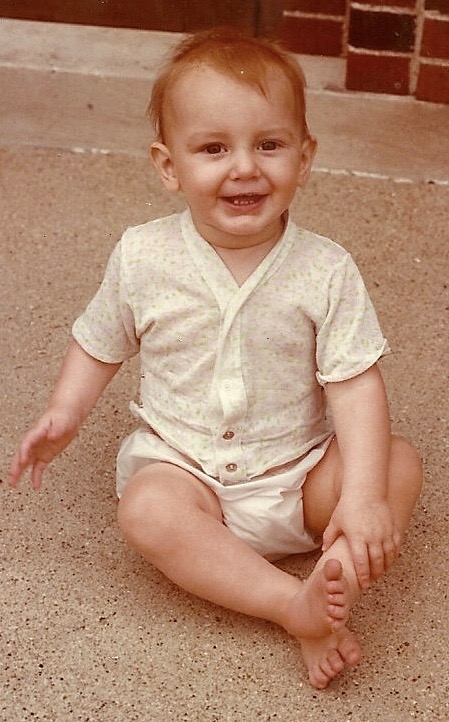

David

This is David (not his real name), one of several children we fostered in the late ’70’s and early 80’s. David lived with us the longest of any of our foster children. He came to us after being removed from his family by CPS. The picture is how I remember David when he came to our home. He was always smiling and seemed to be a happy child.

Not long after he arrived, he fell and bumped his head. It was a nasty bump and we immediately reacted to comfort and console him, expecting hm to wail and cry. We were shocked when David showed no reaction, looked at us and smiled. Perplexed, we had no understanding or experience to call on. We later learned David’s parents did not permit him to cry and punished him when he did so, whether hungry, injured or otherwise. He learned that smiling was good and crying was bad.

Living with a “normal” family gradually conditioned him to react in a more normal fashion. He never became a normal spontaneous kind of child. I will never forget the time he returned from a family visit. His demeanor has markedly different than when left for the visit. Trying to connect with him and reassure him, he remained stoic. Finally, a light flickered in his eyes and he looked at me and said, ” I love you”. I’ll never forget that moment.

Eventually adopted by a family at church, we have been able to see him grow into an adult. There is much more to his story. His life has been extremely difficult but he just keeps smiling, never forgetting the lessons his parents taught him.

Thoughts on the loss of Lament

Brueggemann’s essay written in 1986 asserts lament has been lost as apart of Christian faith and worship. He attributes that loss to a failure to use the lament psalms as they were intended. I trust his assessment of faith and worship at the time he wrote. In 20+ years since, I believe lament, as a part of faith and worship, continued to diminished and been lost in some spheres of western Christianity. While there are some segments where lament remains an integral part of faith and worship, the locus of loss appears to be Evangelical Christianity and related groups on the margin of evangelicalism.

While not diminishing the the role of lament Psalms, or lack there of, in the loss of lament, I believe loss of lament has been accelerated by a proliferation of..

“churches [that] have been turned into celebration centers so that prayers of anguish, lament, and anger are not given space. Without realizing it, we bottle up our anger and fears, put on a happy face, and try to clap our hands like those around us.” (JD Walt)

No matter why lament has been lost, Brueggemann’s analysis of the cost of that loss rings true today.

Despite Brueggemann’s states “Lament occurs when the dysfunction reaches an unacceptable level, when the injustice is intolerable and change is insisted upon.”

Pandemic, economic and racial strife have combined to create “dysfunction and injustice at an unacceptable level.” Tragically, lament has been absent in much of Evangelical Christianity.

I perceive lament to be a leading indicator of churches who lean into social justice. Conversely, churches who are silent or reluctant to speak out against injustice have little or no room for lament.

I believe there are many “David’s” in churches today. People disabused of any notion lament is a part a healthy relationship with God. No matter what happens, they just keep smiling.

Brueggemann’s statement: “The absence of lament makes a religion of coercive obedience the only possibility”. deserves critical examination.

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Psalm 22)

…It is no part of the Christian vocation, then, to be able to explain what’s happening and why. In fact, it is part of the Christian vocation not to be able to explain—and to lament instead. As the Spirit laments within us, so we become, even in our self-isolation, small shrines where the presence and healing love of God can dwell. And out of that there can emerge new possibilities, new acts of kindness, new scientific understanding, new hope…

N. T. Wright