“Someone who thinks the world is always cheating him is right. He is missing that wonderful feeling of trust in someone or something.” – Eric Hoffer

metaphysical belonging,

— a sense that your life fits into a broader scheme of meaning and eternal values.

If you lack metaphysical belonging, you have to rely on social belonging for all your belonging needs, which requires you to see your glorious self reflected in the attentions and affirmations of others. This leads to the fragile narcissism that Lasch saw coming back in 1979: “The narcissist depends on others to validate his self-esteem. He cannot live without an admiring audience. His apparent freedom from family ties and institutional constraints does not free him to stand alone or to glory in his individuality. On the contrary, it contributes to his insecurity.”

David Brooks

Discover Joy

God, who is forever pouring out God’s whole being from all eternity, wants you to flourish. God wants you to be filled with joy and excitement and ever longing to be able to find what is so beautiful in God’s creation: the compassion of so many, the caring, the sharing. And God says, Please, my child, help me. Help me to spread love and laughter and joy and compassion. And you know what, my child? As you do this—hey, presto—you discover joy. Joy, which you had not sought, comes as the gift, as almost the reward for this non-self-regarding caring for others.

Dalai Lama

Cosmic Dance

When we are alone on a starlit night; when by chance we see the migrating birds in autumn descending on a grove of junipers to rest and eat; when we see children in a moment when they are really children; when we know love in our own hearts; or when, like the Japanese poet Bash? we hear an old frog land in a quiet pond with a solitary splash—at such times the awakening, the turning inside out of all values, the “newness,” the emptiness and the purity of vision that make themselves evident, provide a glimpse of the cosmic dance.

Thomas Merton

Memory

We honor pain through memory and we know that people die twice—the second time when no one on earth still speaks their name.

In Judaism God is called Zochair kol Hanishkachot—the one who remembers all things forgotten.

Hebrew has a word that applies only to bereaved parents, shakul. Can one conceive of a history so studded with such loss that there needs to be a designated word?

For the Jewish people amnesia is not an option. Jewish memory is both a tribute and a harbinger. It is what we owe to God, and to those who suffered and those who died. The dead should not be forgotten in the press of the everyday. The poignancy of loss cannot be fully calmed by the blanket of passing time.

David Wolpe

Heartbreak

Heartbreak is about crushed expectations. The problem is that we’ve made romance into such a fantasy that anything short of a Hallmark movie feels like failure. We’ve created generation after generation more in love with this idealized love than with the person. The inability to distinguish this is what causes so much pain.

Why don’t we have high school classes about romantic relationships? We could separate the fantasy from the reality to forewarn our children so they can better handle the flood of hormones and peer pressure. Instead, we give them useless clichés like, “When it’s love, you’ll just know.” While that may be true, most people “just know” many times—and are wrong.

Kareem Abdul Jabbar

Modern World

The modern world is a culture of “fatherless children” (sometimes quite literally). The past (and thus the place and source of our origins) is always seen as something to be overcome. The notion of “progress” includes a forgetting of the past and the reduction of its power in our lives. We seek to self-create and self-define our lives as though we had no source outside of ourselves.

Fr Stephen Freeman

Cultural Christianity

When we insert religion inside of culture, culture wins every time. Most of us are Americans or our nationalities first, and then maybe, once in a while, we are Christians. That’s just obvious—it’s our cultures that form us. We want to believe, we keep pretending we believe, but we really don’t.

Richard Rohr

Scripture

The purpose of Scripture is to not to get a passing grade in Religion 101, rather, the purpose of Scripture is to bring people to believe in Jesus, to come to Jesus, to grasp hold of Jesus, to rest in the one whose yoke is easy and whose burden is light (Matthew 11:30)

Michael Bird

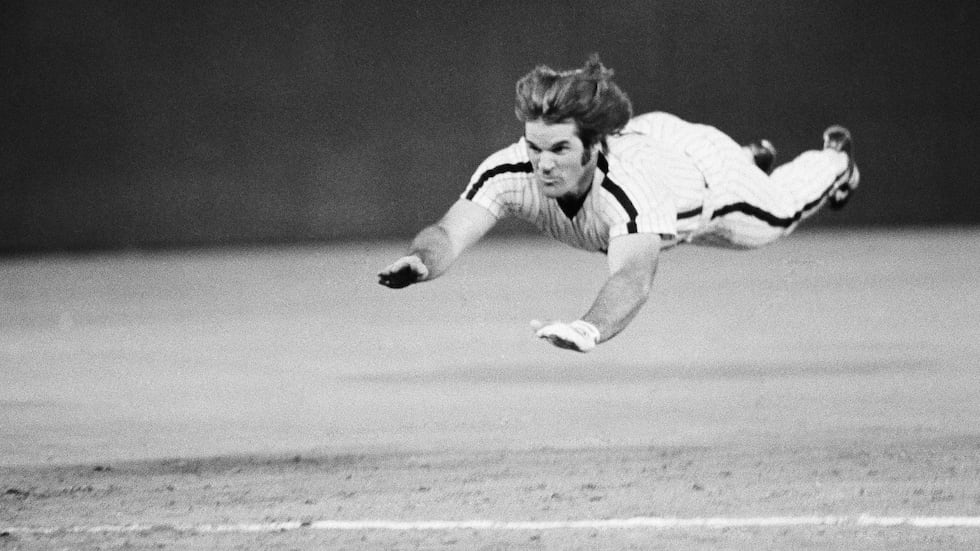

The Irony of Infamy

By the time Rose’s 24 -year career came to an end in 1986 he had become MLB’s all-time leader in hits, games played, at bats, singles, and outs. He was Rookie of the Year, won three World Series championships, three batting titles, two Golden Glove Awards, and one Most Valuable Player Award. He also made 17 All-Star appearances at an unequaled five different positions: first base, second base, third base, left field and right field.

…eighteen months after Rose was banned from baseball and the same year Rose would have been first eligible for the Hall of Fame, its directors voted to exclude individuals on baseball’s permanently ineligible list. This new rule prevented Rose from ever being admitted to the Hall of Fame.

“What, are they waiting for me to die?” Rose repeatedly would say of his chances of getting into the Hall of Fame. “Wouldn’t that be horrible if I died next week and then next year they reinstated me?”

Well, he’s dead, but the controversy continues.

If, some day, he is inducted to the HOF, will he be remembered for baseball or betting?

Reverberation from the Echo Chamber

The Importance of Being Wrong

A whole lot of us go through life assuming that we are basically right , basically all the time , about basically everything : about our political and intellectual convictions , our religious and moral beliefs , our assessment of other people , our memories , our grasp of facts . As absurd as it sounds when we stop to think about it , our steady state seems to be one of unconsciously assuming that we are very close to omniscient .

Far from being a sign of intellectual inferiority , the capacity to err is crucial to human cognition . Far from being a moral flaw , it is inextricable from some of our most humane and honorable qualities : empathy , optimism , imagination , conviction , and courage . And far from being a mark of indifference or intolerance , wrongness is a vital part of how we learn and change . Thanks to error , we can revise our understanding of ourselves and amend our ideas about the world .

... it is ultimately wrongness , not rightness , that can teach us who we are .

Schulz, Kathryn. Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error

The above quotes capture the paradox each of us find ourselves in as we strive for meaningful and authentic lives. An unrelenting pursuit of rightness is pitted against our incontrovertible fallibility. Amazingly, left to our own devices, rightness will almost always win out.

Our desire for rightness leads us to echo chambers where our “rightness” is amplified and error is filtered out. Like a butterfly from a cocoon, we emerge in the beauty of our rightness, confirmed in our infallibility.

The cost of rightness can be high.

Avoidance of controversial issues or alternative solutions creates a loss of individual creativity, uniqueness and independent thinking. Rightness binds and blinds us.

An “illusion of invulnerability” (an inflated certainty of our rightness) can prevail.

Stereotyping of, and dehumanizing actions toward, dissenting persons can develop. As true believers we can produce fantasies that don’t match reality.

Interpersonal communication outside our echo chamber is stifled. Immersion in the

comfortable confines of an echo chamber may result in significant losses, not the least of which, can be family and community relationships.Echo chambers reinforce our natural

tendency to restrict our relationships rather than expand our social interactions.

Residing within an echo chamber strips our lives of serendipity and wonder. We trade off the opportunity to engage the endless diversity of the world around us.

STILL ON THE JOURNEY