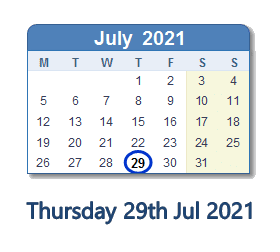

1,102 days ago an unexpected medical trauma brought me to the brink of death. By the providence of God I survived.

“It’s an open question whether a full and unaverted look at death crushes the human psyche or liberates it.”1Junger, Sebastian. In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife (p. 74). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

For me, it has been liberating, an occasion for memento mori (“Remember! You will die!”); abolishing an illusion of immortality and producing a new relationship with death and dying. .

…death is not something to be denied, avoided, or even begrudgingly accepted. Death makes the expanse of a lifetime finite and therefore precious. 2Katherine Wolf -Devotionals Daily

I continue to pursue the subject of death and dying.

Could there be a more relevant subject for a living being?

Some, particularly Christians, say life after death is most important but I contend as long as people believe they are immortal, life after death is irrelevant.

The closest thing to morality in the modern world is oftentimes to avoid making people uncomfortable, unless of course it’s making people uncomfortable about making other people uncomfortable. But if death makes people uncomfortable—and it sure does—then it is very tempting for Christians to want to soften the blow as well.

Fr Stephen Freeman Second Thoughts on Success

“The greatest gift that people can accept at any age is that we’re on borrowed time, and they don’t want to squander it on stupid stuff,”

Anne Lamott

The only clear memory I have from my near death encounter, is seeing kaleidoscope like images of brilliant colors.

STILL ON THE JOURNEY

- 1Junger, Sebastian. In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife (p. 74). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

- 2Katherine Wolf -Devotionals Daily